Kleopatra

I a. pr. Kr., Senovės Egipto civilizacija

Manoma, kad parfumerijos ištakos slypi Senovės Egipte. Kvepalų pavadinimas (agliškai „perfume“) yra kilęs iš lotyniško – „per fumus“ „per dūmus“. Iš tiesų, seniausi pasaulio kvepalai buvo gaminami jau prieš 4000 metų smalkalų pavidalu iš dervų, prieskonių, džiovintų žolelių, vyno medaus ir kt. Šiais smilkalais buvo smilkomi plaukai ir drabužiai, kurie ilgam įsigerdavo dūmų kvapo.

Senovės Egipto kultūroje kvapai – ypatingai svarbi egiptiečių gyvenimo ir kultūros dalis, o kvepalai buvo žmogaus socialinio statuso išraiška. Stipriu aromatu galėjo kvepintis tik karalienė, o saldūs kvapai buvo skiriami dievams.

Jei Senovės Egipto parfumerijos menas turėtų atvaizdą, jis neabejotinai vaizduotų Kleopatrą, kuri be galo mėgo kvepintis, dievino rožes.

Gyva legenda apie tai, kad pučiant lengvam vėjeliui, Kleopatros kvepalai krantą pasiekdavo anksčiau, nei žmonės pamatydavo jos laivą, mat nuo jo dvelkdavo Damasko rožių kvapas, kuriuo buvo pakvepintos laivo burės.

Daugelis Senovės Egipte naudotų kvapiųjų medžiagų parfumerijoje naudojami iki šiol: jazminas, mira, frankincensas, lelijos, rožių aromatai Tuo metu kurtų aliejinių kvepalų pagrindinės sudedamosios dalys: alyvuogių aliejus, mira, cinamonas, kardamonas.

Šaltiniai:

- Egiptologės Dora Godsmith paskaitos medžiaga „Kyphi kvepalų atkūrimas“, 2022 m.

- https://perfumesociety.org/cleopatras-fragrance-finally-recreated/ žiūrėta 2023-08-23

- https://perfumesociety.org/scented-snippets-fascinating-facts-from-the-history-of-fragrance/ žiūrėta 2023-08-23

- Mandy Aftel “Essence and alchemy”, 2022

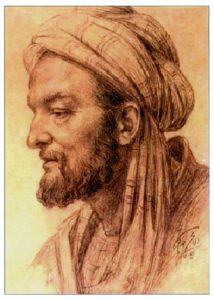

Avicena

XI a., Arabija/Persija

Kol Europa išgyveno tamsiuosius Viduramžius, arabų šalys mėgavosi filosofijos, literatūros, mokslo, medicinos Aukso amžiumi.

Avicena (Ibn Sina) – persų kilmės arabiškai rašęs filosofas, gydytojas, ankstyvosios medicinos tėvas, užrašęs Medicinos kanonus, kuriais medicina naudojosi net iki XVII a.

Manoma, kad arabai eterinius aliejus distiliavimo būdu išgaudavo dar VIII–IX a., o persų išminčius ir alchemikas Avicena šį distiliavimo garais procesą XI amžiuje ištobulino ir aprašė.

Sveikatinimuisi Avicena plačiausiai pritaikė rožių vandenį. Kvapai arabų kultūroje tuomet buvo neatsiejama kūno ir dvasios gerovės dalis. Islamo religija teigia, kad Pranašas pirmenybę teikia maldai, žmonoms ir kvapams. Rožių vanduo tebėra populiarus šventyklų valymui, asmens higienai ir maisto gaminime. Dėl itin didelės kvapiųjų augalų gausos arabijos šalyse, distliavimas neapsiribojo vien rožėmis.

XV a. augalų distiliavimo technologija atkeliavo į Europą: distiliavimo aparatai atsiranda kiekviename dvare ir vaistinėje, distiliuojami augalų vandenys kvepalams ir vaistams gaminti, aplinkai ir drabužiams kvepinti.

Distiliavimas iki šių dienų naudojamas kaip šiuolaikinės aromaterapijos pagrindas.

Šaltiniai:

- Noah Gordon. “Gydytojas. Avicenos mokinys”, 2016

- https://www.carrementbelle.com/blog/en/2022/03/30/the-mythical-cities-of-perfume/

Vengrijos karalienės vanduo

Viduramžiai, Vengrija

Pasakojama, kad 1380 m. Vengrijos karalienei Elžbietai vienuolis padovanojęs kvapaus skysčio. Septyniasdešimtmetė valdovė nuolat skundėsi bloga sveikata, bet vos tik paragavusi šio skysčio nuoviro (tuo metu kvepalais ne tik kvepinosi, bet ir vartojo kaip vaistus į vidų), ji tuojau atgavo jėgas. Karalienė atrodė taip pajaunėjusi, kad Lenkijos karalius nedelsdamas paprašė jos rankos.

Istorijos šaltiniai tokios karalienės nemini, tad ši istorija labiau legenda nei tikrovė. Bet Vengrijos karalienės vanduo – iš tiesų egzistavo ir pasižymėjo tuo, kad tai pirmieji kvepalai Europoje, pagaminti su alkoholiu. Manoma, kad Vengrijos karalienės vandens atsiradimą lėmė jo dezinfekcinės savybės, kurios padėjo kovoto su buboniniu maru, 1346-1350 m. nusinešusiu gausybę europiečių gyvybių.

Pagrindinis Vengrijos karalienės vandens ingredientas – rozmarinas, taip pat čiobrelis, vynas, o vėliau ir levanda, šalavijas, mairūnas, nerolis, citrina.

Kvepalų sudėtyje naudota: rozmarinas, bergamotė, levanda, frankincensas, kojakas.

Šaltinis:

- Fabjena Pavia „Kvepalų pasaulis“, 1998

Barbora Radvilaitė

Renesansas, Lietuva

Barbora Radvilaitė savo vaikystę leido puošniame Radvilų dvare, Vilniuje, ant Neries kranto. Barboros namus supo obelų sodas, vyšnių alėjos, gėlynuose skendėjo tvenkiniai. Barboros tėvas – Jurgis Radvila – ėjo maršalkos pareigas Valdovų rūmuose, kurie tuo metu spindėjo prabanga ir Renesanso grožiu bei niekuo neatsiliko nuo kitų Europos dvarų.

Į ponų stalus tuomet buvo tiekiami tokie skanėstai kaip žali ir kepti vaisiai, taip pat iš pietų kraštų atvežtos razinos, migdolai, figos. Didikų virtuvėse buvo naudojami prieskoniai – pipirai, imbieras, šafranas, gvazdikėliai, cinamonas. Mylimojo Žygimanto Augusto paliepimu Barborai Radvilaitei kasdien būdavo pristatoma labai brangių apelsinų (šiuos gražuolė labai mėgo) ir kriaušių. Žodžiu, ko Barbora norėdavo, tą ir gaudavo.

Be to, Barboros dėdė Mikalojus Radvila (Vilniaus vaivada), įsteigė Vilniuje greičiausiai pirmąją „laisvąją vaistinę“, kurioje buvo prekiaujama ir kvepalais. Tad Barbora Radvilaitė galėjo ne tik puoštis, bet ir kvepintis pagal to meto Europos madas.

Barbora Radvilaitė nėra tipiška Renesanso moteris, nes itin mėgo švaros apeigas, kai tuo metu Europoje didikai prausdavosi ne daugiau kaip keliskartus per metus. Barbora prausdavosi pašildyto vandens kubile ilgai ir dažnai. Šį įprotį iš mylimosios perėmė ir Žygimantas Augustas. Jis, motinos pastebėjimu, pamilęs Barborą, „įsimylėjo kvepalus ir vonią“. Tiesa, istorikė M. Matušakaitė savo studijoje pastebi, kad net pats Žygimantas Augustas stebėdavosi ilgomis mylimosios maudynėmis pirtyje.

Renesanso laikotarpiu kvepalai dažnai buvo nešiojami pomanderiuose – apvaliuose atidaromuose papuošaluose su skylutėmis, pro kurias sklido aromatas.

Kairėje: Osmoteque (Didžiausias pasaulyje kvapų archyvas, Versalis) publikuotas paveikslo frakmentas su Renesanso pomanderiu.

Dešinėje: Barboros paveikslas, kuriame prie diržo kabo pomanderis. Paveikslas tapytas 1547-1548 m. netrukus po Žygimanto Augusto ir Barboros Radvilaitės slaptų vestuvių. Manoma, kad Barbora tuo metu buvo nėščia.

Didikai tuo laikotarpiu dievina pirštines, tačiau jos siuvamos iš prastai apdirbtos odos, todėl skleidžia nemalonų kvapą, tiesiog dvokia, todėl šlakstomos stipriais kvepalais.

Deja, nėra išlikusios informacijos apie Barboros Radvilaitės kvepalus, kuriais ji kvepinosi savo klestėjimo laikais, bet pavyko aptikti kvepalų receptą, kuriuos jai pagamino daktaras, kuomet Barbora sunkiai sirgo ir net gulėdama ligos patale stengėsi spinduliuoti žavesį.

Prieš mirtį karalius buvo pažadėjęs žmonai pargabenti jos palaikus į Vilnių. Tą ir padarė. Kelionė truko beveik mėnesį. Pats karalius jojo raitas paskui karstą, o keliaujant per miestus, nulipdavo ir eidavo paskui kartą pėsčiomis. Birželio 23 d. Barbora Radvilaitė buvo palaidota Vilniaus katedros rūsiuose.

Sudedamosios dalys: gvazdikėliai, muskatas, kardamonas, ambra, dervamedis, muskusas, rožių ir levandų vanduo.

Šaltiniai:

- Raimonda Ragauskienė “Barbora Radvilaitė”, 1999

- Marija Matušakaitė Karalienė Barbora ir jos atvaizdai, 2008, “Versus aureaus”

- Alfa.lt 2012-05-29 “Kaip Barbora Radvilaitė atrodytų šiandien“

- Delfi.lt 2016-01-24 Kaip mirė gražiausia Lietuvos moteris (II) https://www.delfi.lt/sveikata/sveikatos-naujienos/kaip-mire-graziausia-lietuvos-moteris-ii-70193548 žiūrėta 2023-08-23

- “Metalinės aprangos detalės ir papuošalai Vilniaus žemutinės pilies tyrinėjimų duomenimis“ https://www.ethnicart.lt/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=308&Itemid=440&lang=lt Žiūrėta: 2023-08-21

- https://www.moteris.lt/lt/veidai/g-37369-barbora-radvilaite-kodel-vyrai-kraustesi-del-jos-is-proto Žiūrėta: 2023-08-21

- Большая, 1986 – Большая иллюстрированная энциклопедия древностей // Прага, 1986

Mumtaz Mahal

XII a., Mogolų imperija (Indija)

XVII a. legendinė imperatoriaus Džachanšacho ir jo žmonos Mumtaz Mahal meilės istorija įkvėpė sukurti ne vieną meno kūrinį. Šiai istorijai dedikuoti ir garsieji Guerlain kvepalai „Shalimar“, bet šį kartą ne apie juos.

Prieš tampant imperatoriumi, dvidešimtmetis princas Khurramas turguje susipažino su jauna mergina, vardu Arjumand Banu. Sužavėtas jos grožio, jis vedė šią nekilmingą merginą ir suteikė jai Mumtaz Mahal vardą, kas reiškė „rūmų brangakmenį“. Po vestuvių imperatorius ir Mumtaz buvo neišskiriami. Ji padovanojo Džachanšachui 13 vaikų ir mirė gimdydama 14-ąjį vaiką. Jai buvo 39 metai. Jos mirtis slėgė Džachanšachą ir imperatorius pastatė Tadžmahalą savo žmonos ir jų nemirtingos meilės atminimui.

Nepavyko aptikti tikslių receptų, kuo kvepinosi Mumtaz Mahal, tad kvepalai gimė išanalizavus to meto istoriją ir ypatingus indiškus kvepalus – atarus, kurie naudojami parfumerijoje iki šiol. Kai 1600-ųjų pradžioje buvo atrasta atarų gamybos technologija, „attar“ kvepalai buvo siejami beveik vien tik su rožių ataru, kuris pradėtas eksportuoti į Europą. Bet tik nedaugelis žinojo, kad be visame pasaulyje žinomo rožių ataro, Indija turėjo neįtikėtiną kvapiųjų žaliavų įvairovę, kurias distiliavo, ekstrahavo, maceravo arba išgavo enfliuražo būdu. Tad parfumeriams čia buvo prieinama gausybė kvapų ir esencijų.

Mumtaz Mahal gyveno kvapniame amžiuje, Mogolų imperijos epochoje, kada kraštas klestėjo. Mogolų imperatoriai ir princai dievino kvapus ir kvepalus, todėl skatino ir investavo į atarų gamybą bei jų eksportą. 1526 m. pradėtas plataus masto rožių ataro eksportas į Europą ir kitas šalis, o XVI-XIX a laikomas atarų gamybos Aukso amžiumi.

Kvepalai:

Pagrindinės natos: kardamonas, kedras, rožė, jazminas, vetiverija, degintos žemės ataras

Atarų gaminimo procesas: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1779779619077701

Liudvikas XIV

Barokas, Prancūzija

Nuo Renesanso laikų manyta, kad vanduo perneša marą ir kitas ligas. Tad žmonės beveik nesiprausė. XVII a kvepalai tampa labai populiarūs, tai galima pavadinti „išprotėjimu dėl kvepalų“. Deja, su higiena tai nėra susiję, greičiau – priešingai, kvepalai turėjo nustelbti aplinkos smarvę. Pudros ir kvapieji vandenys persunkia Karaliaus Saulės dvariškių veidus ir perukus. XVII a. galybė medžiagų, vartojamų kvepalams gaminti, pratutinama jazmino, rožių, tuberozų kvapais.

Vieni šaltiniai teigia, kad Karalius Saulė nemėgo praustis, bet kituose šaltiniuose rašoma, kad jis nemėgo tik daktarų išrašytų vonių, kurios buvo šaltos ir kvepėjo vaistinėmis žolėmis. Sakoma, kad po Versalio rūmais turėjo įsirengęs turkišką pirtį, kur nuo vaikystės leisdavo laiką su mama, o vėliau su meilužėmis.

Net jei karalius prausdavosi ir ne kasdien, bet tris kartus per dieną keisdavo baltinius. Skalbiniai, kaip ir visa kita rūmuose buvo gausiai kvepinama. Tik koridoriai dvokė išmatomis, nes 10 000 to meto Versalio gyventojų tualetų labai trūko.

Kas rytą Karalius prašydavo iškvepinti jo baltinius „Aqua Angeli“ (angelų vandeniu), kuriame muskatas, dervamedis, gvazdikėliai, benzoinas, alavijas ir rožių vanduo. Vakariniai karaliaus kvepalai dar buvo papildyti jazminų ir nerolio vandeniu su žiupsneliu muskuso. Šiame skystyje buvo išmirkomi baltiniai ir išdžiovinami.

Ilgainiui nuo stiprių kvapų Liudvikui XIV išsivystė alergija, ir gyvenimo pabaigoje galėjo mėgautis tik švelniu nerolio vandens aromatu, kuriuo kvepindavo savo drabužius ir kambarius.

Šaltiniai:

Marija Antuanetė

Švietimo epocha, Prancūzija

Filosofijos ir revoliucijos epocha yra taip pat ir kvepalų suklestėjimo metas. Liudviko XV dvaras buvo vadinamas „Iškvepintu dvaru“, nes įvairiausius kvapus jame skleisdavo ne tik dvariškių veidai, bet ir jų drabužiai, vėduoklės, net jų baldai.

Šiame kvapniame amžiuje karaliavo Liudvikas XVI ir Marija Antuanetė – prabangos ir išlaidumo simbolis. Karalienės garderobe ne tik prabangiausia apranga, bet gausybė kvepalų. Dėl karalienės dėmesio varžėsi daugelis to meto parfumerių – be atlygio siųsdavo karalienei savo kurtus kvepalus, o pastaroji išsirinkdavo jai labiausiai patinkančius ir jiems išleidavo didžiules sumas. Marijos Antuanetės kvepaluose dominuoja gėlės, o tai reikšmingas kvepalų virsmas po Liudviko XIV kvepalų.

Karališkoji šeima nujautė revoliucijos nuotaikas, tad 1791 m. nusprendė bėgti iš Paryžiaus. Šiai kelionei Marija Antuanetė itin kruopščiai ruošėsi ir dar prieš išvykdama išsiuntė milžinišką siuntą kvepalų ir kosmetikos priemonių. Šios priemonės buvo oficialiai įvardintos kaip dovana seseriai Madam Campan į Briuselį, bet iš tikrųjų karalienė negalėjo išsiskirti su savo mylimom kosmetikos priemonėm ir siekė jomis apsirūpinti bene visam likusiam gyvenimui. Jos mėgiami parfumeriai Fargeon ir Haubigant gavo tokio dydžio užsakymus, kad neturėjo pakankamai žaliavų jiems skubiai įvykdyti.

XVIII a. kvapiosios medžiagos laikytos įvairiausių formų induose. Aromatizuotu tualetiniu vandeniu sudrėkinta kempinė dedama į paauksuoto metalo indus. Skysti kvepalai pilami į grakščius Liudviko XIV stiliaus flakonus. Prancūzijoje 1765 m. įkurta Bakara stiklo manufaktūra gamino vien kvepalų flakonus. Jų krištolo dirbiniai netruko išgarsėti, jų šlovė dar neišblėso iki šiol. XVIII a. yra neseserų, mažų dėžučių, kuriuose laikomi kvapieji aliejai, epocha. Be mažo piltuvėlio flakonams pildyti į neseserus dėti pieštukai, dantų šepetėliai ir net „liežuvio gremžtukai“.

Vienas iš Marijos Antuanetės parfumerių Jean-Louis Fargeon sukūrė kvepalus Parfum du Trianon, kurie turėjo priminti karalienei jos mylimų rūmų aromatą. Kurdamas šiuos kvepalus, jis aprašė ir sudėtines dalis bei jų reikšmę kvepaluose:

Apelsinmedžio žiedai (nerolis) – balti tvirti žiedai, pripildyti aromato ir gaivos, tarsi zefyras ar vaiko bučinys.

Levanda naudojama sušvelninti nerolio aromatą.

Pridėjo savo spausto citrinų ir bergamočių aliejaus, kuris turėjo būti karalienei pažįstamas, todėl sukelti jaukius prisiminimus.

Galiausiai – lašelis galbanumo, kuris iškėlė žalią kvepalų natą ir sujungė viršutinę ir širdies natas. Šį kvapą parfumeris pajunta kaskart sulaužęs žolės stiebą, o karalienei jis reikštų etiketo sulaužymą ir sielos išlaisvinimą bei pakilimą aukščiau pasaulio taisyklių.

Netrukus pasireiškia irisas, kuris graikų mitologijoje siejamas su Dzeusu. Iriso potėpis praturtina kvepalus „stebuklingomis dulkėmis“, kurios tarsi aureolė apgaubs karalienę. Iriso kvapas skleidė šilumą ir suteikė kvepalams maloningą aromatą. Parfumeris žinojo, kad irisas pastirpins ir kvapiųjų našlaičių aromatą, kurį karalienė taip mėgo.

Našlaičių aromatas – šviežias ir spontaniškas, kaip pati karalienė jaunystėje. Tapusi karaliene, turėjo išmokti slėpti savo tikrąją prigimtį ir pasitelkti visas savo gudrybes, tad buvo miela prisiminti praeitį. Be to, sakoma, kad našlaičių aromatas atgaivina prisiminimus apie praeities meiles.

Širdies natoje parfumeris išmoningai įkomponavo tuberozą, kuri turėjo simbolizuoti triumfą, galią ir stimuliuoti erotiškumą.

Visą kompoziciją apjungia ambra ir muskusas, kurie suteikia jausmingumo, animalistinio užsidegimo, o benzoinas – šilumos ir ilgalaikiškumo.

Šis tvyrantis ore aromatas turėjo būti tarsi slaptos meilės antspaudas.

Kvepalų natos: galbanumas, nerolis, bergamotė, irisas, rožė, tureroza, levanda, benzoinas, kvapioji našlaitė, ambra, labdanas.

Šaltinis:

- Elisabeth de Feydeau, „A scented palace. The secret history of Marie Antuanette‘s perfumer“, 2018

Napoleonas Bonapartas

Švietimo amžius, Prancūzija

Didžioji Prancūzijos Revoliucija buvo didelis sukrėtimas parfumeriams, kurie neteko didelės dalies savo kientų, kurie dėl represijų paliko šalį arba gyveno tremtyje. Tačiau parfumerijos padangėje atsirado odekolonas. Bene žymiausas odekolno gerbėjas – Napoleonas Bonapartas, suvartodavęs po 50 buteliukų per mėnesį – jis ne tik kvepinosi, bet ir lašindavo jo ant cukraus gabalėlių.

Napoleonas Bonapartas dievino odekolono gaivą, šlakstydavo juo pečius ir sprandą. Jam ypač patiko rozmarino – vienos iš pagrindinių sudedamųjų dalių – aromatas, kuris jam priminė gimtąją Korsiką. Kasdien tarnas ištrindavo imperatorių nuo galvos iki kojų Žano Marijos Farino pagamintu odekolonu. Parfumeris net sukūrė ritinėlio pavidalo flakoną, kurį imperatorius įsidėdavo į aulinius batus.

Žanas Marija Farina sakė: „Atradau kvapą, kuris man primena pavasario rytmetį Italijoje, kalnų narcizus ir apelsinmedžių žydėjimą po lietaus“. Parfumeris gamino kvepalus pagal stebuklingą receptą, kurį man pavyko atrasti, bei itin rūpinosi eterinių aliejų kokybe. Farina žinojo, kad tik aukščiausios kokybės aliejai sukurs tobulą kvapą, todėl skrupulingai testuodavo kiekvieną aliejaus partiją ir duodavo nurodymus eterinių aliejų tiekėjams apie augalų priežiūrą, rinkimą ir distiliavimą.

Napoleonas žavėjosi ir savo žmonos „eau naturel“ („natūralus vanduo“, turima galvoje natūralus kvapas). Grįždamas iš mūšio pasiųsdavo žmonai žinutę, „Nesiprausk, po aštuonių dienų aš grįšiu pas tave“. Bet nepamiršdavo jai nupirkti ir kvepalų su jazminais, kuriuos ji labai mėgo.

Žozefina jautė potraukį stipriems kvapams, ji vadinta pamišėle dėl muskuso. Jos kambarys Malmezone buvo taip stipriai persismelkęs įvairiausių kvapų – muskuso, civeto, vanilės, ambros, kad net po septyniasdešimt metų juos dar buvo galima užuosti. Ne kartą imperatorius yra išbėgęs iš Žozefinos buduaro, nes jam atrodė, kad stinga oro.

Po Napoleono valdymo pasibaigė natūralios parfumerijos era, buvo sukurtos pirmosios sintetinės kvapų molekulės, kvepalų gamyba ženkliai keitėsi, buvo sukurta gausybė naujų kvapų, kurie naudojami iki šiol.

Kvepalai: odekolonas.

Kvepalų sudėtyje naudota: rozmarinas, citrina, bergamotė, nerolis, kedras, laimas, petitgreinas.

Šaltiniai:

- Fabjena Pavia „Kvepalų pasaulis“, 1998

- Bernhard Kuhlmann, „‘Jedenfalls schmeckt Eau de Cologne besser als Petroleum’,” Oh! De Cologne. Die Geschichte des Kölnisch Wasser, ed. Werner Schäfke (Cologne: Wienand, 1985) 9-52, p. 27.

- https://perfumesociety.org/history/napoleon-josephine-and-a-giant-bill-for-cologne/